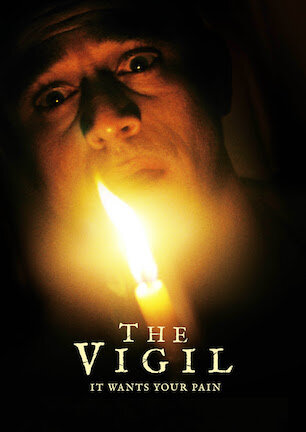

Studio: Blumhouse/IFC Midnight

Director: Keith Thomas

Writer: Keith Thomas

Producer: Raphael Margules, J.D. Lifshitz, Adam Margules

Stars: Dave Davis, Menashe Lustig, Malky Goldman, Fred Melamed, Lynn Cohen

Review Score:

Summary:

A troubled Jewish man faces his personal demon in physical form when he agrees to sit with a dead body overnight.

Review:

Yakov faces a crisis of faith on two fronts. The first directly deals with his religion. The second has to do with how little he believes in himself.

Yakov left his orthodox Jewish community not long ago. Adapting to a mainstream lifestyle hasn’t been easy. Handwritten résumés aren’t attractive to prospective employers. Medication and rent compete for limited income. And figuring out how to enter his crush Sarah’s number into his new cellphone may as well be putting a square peg in a round hole.

Although he left behind the payot that used to adorn his head, Yakov did bring the guilt he feels over the tragic death of his little brother Burech. Yakov blames himself for failing to act when the siblings were accosted by anti-Semitic a-holes on the street. Broken by the ordeal, Yakov struggles to reconcile his religious beliefs as well as his self-worth against the reality of a harsh world he isn’t fully prepared for.

Yakov’s former rabbi may have a solution. Hoping to bring Yakov back to the fold, Reb Shulem hires Yakov to be a shomer, a person who sits with a dead body and recites traditional prayers to keep evil away. Yakov doesn’t put much stock in Hasidic customs anymore. However, he needs the money, so Yakov agrees to spend an evening with the body of Mr. Litvak, a reclusive Holocaust survivor, while the dead man’s dementia-afflicted wife mourns upstairs.

It doesn’t take long for the overnight experience to turn into an eerie event. Yakov’s time in the Litvak home sees the young man recoiling from odd noises, flinching at darkness, and outright encountering horrifying apparitions. When he finds an old video Mr. Litvak recorded, Yakov learns he has unknowingly stepped into the lair of Mazzik, a demon who feeds on the personal pain of human hosts. Rather than protect Mr. Litvak on his journey to the afterlife, Yakov’s vigil thus becomes a battle to save his own soul.

That’s a somewhat lengthy summary for a film whose setup is somewhat simple. Relative verbosity feels necessary though, to project an accurate air of how “The Vigil” builds a long bridge of introspective human drama before arriving at its destination of unsettling supernatural spooks.

“The Vigil” is a mood movie through and through. Flickering lights. Fluttering curtains. Shapes in shadows. Stalking slowly in candlelight. Pick your preferred poison for slow burn suspense. “The Vigil” probably has it. Some squirm-inducing visceral sequences, one involving everyone’s favorite: fingernail trauma, come memorably to mind. But this is very much an atmosphere-oriented experience in escalating dread.

If those ingredients aren’t to your liking, connecting to “The Vigil’s” core presents more of a challenge. Yakov’s showdown with a physical demon means to mirror the everyday confrontations his psyche has with his personal one. “The Vigil” almost masquerades as a horror movie when it’s really a personality study about rebuilding one’s identity out of forgiveness, faith, and companionship. Weighty themes that pull from tragedies of incidental deaths and concentration camp atrocities give gravitas to a slim story, though that slimness can make the movie’s scant scares seem trivial if taken purely as a thriller.

“The Vigil” boasts high production values for a low budget. Single setting productions are infrequently blocked, lit, and shot with maximum moodiness in mind as well as this one is. At the same time, frights are formulaic, yet their craftsmanship is more than competent.

It turns out demons are a universal threat no matter the culture. Outside of the brief introduction to this particular funerary ritual, I’m not sure how unique “The Vigil” really is to Judaism, if indeed that was ever writer/director Keith Thomas’s intent. Dave Davis uses friendly fumbling and expressive sadness to fashion Yakov as a relatable Everyman despite his Hasidic specifity, which affirms “The Vigil’s” accessibility for audiences of any background. Because of their straightforwardness, the scares broaden appeal as wide as possible too, though their straightforwardness comes with a “been there, done that” side effect for hardened horror vets. In a nutshell, “The Vigil” writes an excellent essay about dealing with personal trauma that gets a little drowsy due to taking scenic sidetracks on every quiet route to a paranormal pop.

Review Score: 65

Too slow to ever reach a burn, “The Dreadful” doesn’t have many logs capable of catching fire in the first place, let alone a spark to ignite them.