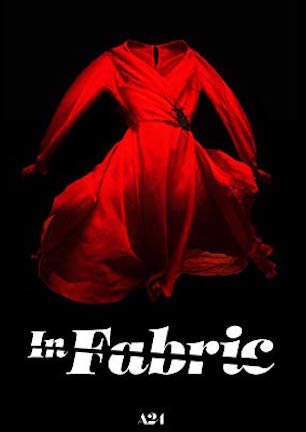

Studio: A24

Director: Peter Strickland

Writer: Peter Strickland

Producer: Andy Starke

Stars: Marianne Jean-Baptiste, Hayley Squires, Leo Bill, Julian Barratt, Steve Oram, Gwendoline Christie, Barry Adamson, Jaygann Ayeh, Richard Bremmer, Terry Bird, Fatma Mohamed

Review Score:

Summary:

A cursed red dress from a cult-like department store haunts the lives of a lonely bank clerk and an emasculated repairman.

Review:

“In Fabric” was written and directed by Peter Strickland, executive produced by Ben Wheatley, and theatrically distributed in the United States by A24. If those names mean anything to you, then they’ve already done the lion’s share of describing the film’s aesthetic with a broad, yet probably not inaccurate, initial impression.

Peter Strickland made a mark in fright film fringe with “Berberian Sound Studio” (review here). Ben Wheatley became similarly synonymous with cryptic cinema through offbeat projects like “A Field in England” (review here). Bannered over titles such as “It Comes at Night” (review here), “The Witch” (review here), and “The Lighthouse,” A24 built their boutique brand by polarizing audiences with black and white color schemes, period pieces, and other arthouse accoutrements that cause chin-strokers to clap hands while unimpressed yawners check their phones with exhausted sighs.

There may not be three better names to list on a trifecta of bizarro moviemaking capable of causing “yes, please!” and “no, not this again” reactions in equal measure. That’s all anyone needs as a starting point for “In Fabric,” and works wonderfully as alternative terms for “slow burn setup, open-ended, experimental,” etc., etc., which go without saying when any of the above are involved.

“In Fabric” regularly reinforces its dreamily miasmic tone. 12 minutes into the movie, after we’ve lengthily gotten to know divorced bank clerk Sheila as a lonely mother to an artist son with a careless girlfriend, Sheila purchases a one-of-a-kind red dress from Dentley and Soper’s department store. Already presented as fostering a cult-like atmosphere for bargain-obsessed shoppers, the retail associates behave like plastic mannequins (cough) and dress like docents working a witch museum in Salem. One of the weird women tells Sheila, “the hesitation in your voice, soon to be an echo in the recesses of the spheres of retail … in apprehension lies the crevices of clarity.”

Obviously, Miss Luckmoore intends to be unsettlingly strange. Still, this manner of dialogue, delivered unironically, indicates the kind of unconscious content the movie mushes around like Play-Doh while only making vague shapes of tangible storytelling.

As much as it is “about” anything, “In Fabric” goes on to document the tale of a wearied woman dealing with the daily disappointments of deadbeat blind dates, patronizing bosses, and disrespect in her home. All the while, the dress inexplicably amplifies casual chaos consuming Sheila’s life. Whether it’s destroying her washing machine or inviting an unleashed dog to viciously maul her, sometimes the dress even causes that chaos.

An actress incapable of being uninteresting, Marianne Jean-Baptiste turns “In Fabric” into an empathetic character portrait of someone tired of failing to catch a break, but determined to manufacture one of her one. As clothing often does however, the dress only permits superficial happiness. Sheila’s unfailing resilience against average adversities both overt and projected makes her arc all the more heartbreaking because she doesn’t know what we do. A haunted item only facilitates doom in a horror movie, even a reservedly satirical one.

It’s a long journey through this slice of Sheila’s ordinary existence. As engrossingly as Jean-Baptiste portrays working class struggles, specifically those targeting women, you’ve got to invest in the futile hope that brightness may eventually lighten Sheila’s load to reap the emotional rewards of her performance. And to not become bored by a two-hour endeavor.

As much time as we spend on Sheila’s mundane minutiae, it apparently isn’t long enough. Seeming like he originally started with a proposal for an anthology and only made it two segments deep, or maybe thought Sheila didn’t contribute enough meaningful material, Strickland abruptly swaps out our protagonist a little over an hour into the runtime.

Peripherally connected to the first half by only the weakest of links, “In Fabric’s” second section follows emasculated appliance repairman Reg Speaks, who possesses the unique power to give people mesmeric orgasms by entrancing them with monotone work order descriptions. At the same time, he lacks the assertiveness to convince his bride-to-be to satisfy his nylon fetish in a side story of indefinable purpose. Forced to wear the dress as a bachelor party gag, Reg inadvertently invites the curse to upend his life much like it did to Sheila.

“In Fabric” often finds itself thematically all over the place while chasing exploratory ideas that never fully come to fruition. Trading Sheila for Reg is one example of the film being unable to stand still (figuratively speaking, it literally does so liberally). It is definitely a trade down too.

It’s not that actor Leo Bill isn’t amusing as Reg. He and his arc both provide blips of engaging entertainment. It’s that Jean-Baptiste is a tough act to follow, and the silly sad sack streak behind Reg’s story doesn’t wash down well after the comparatively serious stakes of Sheila’s.

“In Fabric” reminds me of “Velvet Buzzsaw” (review here) in that I’m not sure if the filmmaker fully thought through his artistic expression or laughingly assumed viewers would invent supposed commentary on their own. Alternatively, it could be that I’m not cinematically sophisticated enough to tune into the subtext. Maybe a middle-aged man who fits the stereotype of not trying things on, much less hasn’t shopped in a department store in a decade, doesn’t possess the perspective to properly process a slyly subversive satire on retail shopping and material objectification, if “In Fabric” actually qualifies as much as its appreciators claim.

In such circumstances of possible purposelessness, a flipped coin lands on its side with a 50/100 because I’m objectively indifferent to the movie. Reduced to a binary reaction, I’m unsure if I even liked “In Fabric” or not. I find it more confused than confusing, indulgently overlong, but visually intriguing due to an incredible 1970s aesthetic that is expertly realized with excellent era recreations of props, settings, and filmmaking styles.

For more insightful musings, or potentially imaginary interpretations of intelligent underpinnings that may not even exist, seek out any of the gushing raves from major outlets who have christened the film with a 95% Rotten Tomatoes aggregate. With a consensus that the film’s “gauzy giallo allure weaves a surreal spell, blending stylish horror and dark comedy to offer audiences a captivating treat,” critics have orgasmed over “In Fabric” like a macabre department store manager masturbating while two minions make a mannequin grow a menstruating vagina during an odd occult ritual.

Oh, did I forget to mention that scene? Never mind citing Strickland, Wheatley, and A24. I should have led by discussing the shot of ropey ejaculate arcing across a black backdrop in slow motion. That’s really the kind of movie we’re talking about when we talk about “In Fabric.”

Review Score: 50

This supposedly preplanned trilogy became a tangled, bloated, inconsistent blob of inconsequential characters, dead ends, and ludicrously lame lore.