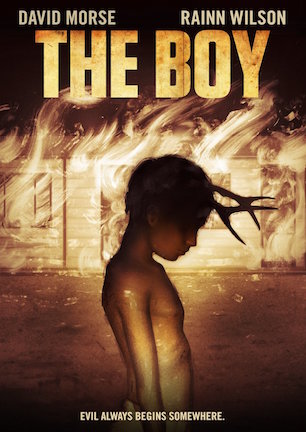

Studio: Spectrevision

Director: Craig William Macneill

Writer: Clay McLeod Chapman, Craig William Macneill

Producer: Daniel Noah, Josh C. Waller, Elijah Wood, Douglas T. Brown

Stars: David Morse, Jared Breeze, Bill Sage, Mike Vogel, Zuleikha Robinson, Aiden Lovekamp, David Valencia, Rainn Wilson

Review Score:

Summary:

A young boy living with his father at an isolated motel finds his fascination with death growing into an even darker desire.

Click here for the 2016 "The Boy" about a doll starring Lauren Cohan.

Review:

Whether using his vending machine chips to bait a makeshift animal trap, or ignoring a Playboy in favor of a dusty ledger that records his roadkill captures, Ted Henley has interests clearly different from most ordinary nine-year-old boys. Condemned to living a forgettable life of solitary anonymity running a roadside motel ghost town with his oblivious father, “The Boy” paints a slowly simmering portrait of how Ted’s frustrated mind develops abnormally from a focused fascination with death into a macabre desire to control its power.

What intrigues most about writer/director Craig Macneill and co-writer Clay McLeod Chapman’s exploration of Ted’s devolution is their intentional sidestepping of a predictable progression arc from childhood innocence to obsessive sociopath. It may be argued if Ted can be considered neglected, but he isn’t abused, bullied, or even unloved at the outset. And while Ted’s home life is unenviable, it is no more broken than that of any average latchkey kid living with a distracted single parent in the overlooked oblivion of blue-collar Middle America.

“The Boy” teases the periphery of a nature versus nurture debate, careful to avoid pointing any singular finger of blame while being otherwise unconcerned with connecting direct lines between cause and effect. Of particular interest is the way Ted constructs his exploratory animal kills to be indirect affairs. The boy doesn’t hold a magnifying glass to an ant much less torture a kitten in his hands the way many burgeoning young serial killers do. Ted manufactures a highway food oasis for random wildlife and waits for speeding cars to do the legwork on his behalf. He isn’t so much outright murdering as he is assisting a scenario that could occur just as easily by serendipitous means, lending a twisted morality to his misdeeds that muddles the lines of enmity and sympathy towards the boy.

Aided by a rain-soaked road in the middle of the night, something more than a soon-to-be-dead deer is inadvertently lured when unsuspecting motorist William Colby unwittingly triggers Ted’s trap and ends up with a totaled car for his troubles. Ted and his father put up the disoriented man in their motel for recovery and it isn’t long before Colby’s cagey evasion of the local sheriff’s questions trips a warning bell that Ted may not be the only one hiding his true nature.

As Ted takes a shine to the odd new tenant, a family with a son the same age stops by for a spell, prompting Ted to perpetuate the motel’s newfound population by secretly disabling their car. Other than boredom, Ted probably isn’t sure why he is so wholly determined to strand wayward travelers. But his curiosity for outsiders soon manifests into unsettling nighttime visits that find Ted looming over occupied guest beds like a snake poised to uncoil. By the time an unruly mob of inebriated teenagers arrives for a prom weekend of property trashing, a perfect storm of all of the above sees Ted suitably primed and provoked to unleash his innermost monster in fiercely explosive fashion.

While the role is too understated to qualify the performance as masterful, Jared Breeze is no less compelling as Ted. He plays the troubled young mind with natural instincts that take the task seriously, and without engaging in any clowning theatrics of clenched teeth, raised eyebrows, or menacing mugging. David Morse, terrific as always, does the same as Ted’s father, somehow taking a character with stereotypical purposing and injecting him with affable humanity that bolts the fiction firmly into the ground.

Effective as a quiet character study, “The Boy” is at its best when atmospheric ambiance pokes through the narrative to captivate on visuals and audio alone. Ted’s tale is one of loneliness and isolation, yet the production is unafraid to maintain his environment as open and accessible. When pool-set playtime between the two boys takes a turn in tone, the camera is content to keep its distance, framing the scene from an unobtrusive position below the waterline instead of artificially inflating tension through claustrophobic close-ups and cutaways. It’s an atypical cinematic style that keeps the unsettling vibe natural yet unfamiliar in concurrent doses.

Jeffery Alan Jones designs a complementary soundscape for the setting that is so impressive, it borders on drawing too much attention to itself. From ambient sounds of noisy insects in the distance to pulse beats provided by blood drips plinking in a metal bucket, the foley work in “The Boy” amplifies the atmosphere more than any individual element through extraordinary attention to detail.

“The Boy” has an ability to taint any scene with sinister portent. Scenes of Ted taking the visiting child on a “don’t tell your parents” trip to a dimly lit drainpipe, or hovering silently over sleeping motel guests, arrive with the anticipatory discomfort of waiting anxiously for a predator to spring upon his prey. But when that doesn’t happen, again and again, the constant teases of terror that never comes begin unraveling the rhythm until interests no longer have incentive to remain vested in the outcome.

Weighing in at 105 minutes, “The Boy” traps itself in a corner by giving its sights, sounds, and story so much room to breathe that the suspense ratchet cannot retain its tightness. The movie has more time than it needs to get where it wants to go, giving excess duration free reign to defuse dread with unfulfilled setups and unnecessary asides.

MILD SPOILER

When the movie loosens its grip on the focus, the themes gradually waver, too. One scene sees Ted kicking a caged chicken to death in a fit of frustration, a moment of shock serving as a transition point in Ted’s metamorphosis, but one not in keeping with the modus operandi of committing acts in the third person, as Ted’s other crimes are. It seems a small point, though it is among several not to be discounted when evaluating how meaningful “The Boy” makes its message.

END SPOILER

Bolstered by captivating performances, but burdened by a pace needing urgency to maintain it as a true thriller, “The Boy” makes the most of its mood before its story becomes carried away with circling the wagons and waiting too long to go on the offensive. The net result is a movie with more than a handful of exceptional building blocks, but missing the mortar to cement it together as a fully functioning blend of commentary and entertainment.

Review Score: 60

“We Bury the Dead” doesn’t have enough meat on its bones to land on a list of top ten zombie films for any of its three release years.