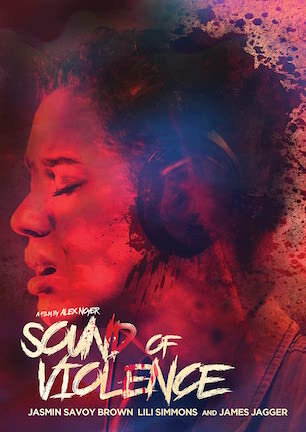

Studio: Gravitas Ventures

Director: Alex Noyer

Writer: Alex Noyer

Producer: Hannu Aukia, Alex Noyer

Stars: Jasmin Savoy Brown, Lili Simmons, James Jagger, Tessa Munro

Review Score:

Summary:

A formerly deaf musician discovers she can see sounds of violence, which inspires her to create music through murder.

Review:

An accident left Alexis deaf as a young child. Miraculously, she inexplicably regained her hearing at age 10. Tragically, it happened in the most horrific circumstances imaginable.

Alexis interrupted her father, a combat veteran suffering from PTSD, in the act of viciously butchering her mother. The girl gave dad a dose of his own brutality by instinctively grabbing a meat tenderizer and swinging it through his skull. That’s when her hearing spontaneously returned, along with a euphoric aural sensation that allowed Alexis to visualize the violent sounds like a tangible hallucination stimulating her senses.

As an adult, Alexis tries keeping this terrible past behind her. She works as a teacher’s aide, secretly carries a candle for her roommate Marie, and pursues her fascination with sound as an experimental musician. Those experiments include odd audio sessions such as recording whip cracks and cries as a dominatrix subjugates her slave. Alexis then creates a soundscape from the pain by turning it into synthesized music.

Like an addict with a drug, Alexis’s desire to mine misery grows insatiable. Sporadic spots of silence indicate Alexis’s deafness is returning. She only finds relief when flashing back to dad’s death, as sounds of violence restore her hearing with a high. Confident she can create a masterful composition from suffering, Alexis becomes so obsessed with these sounds, she’s oblivious to her evolution into a macabre murderer.

“Sound of Violence” isn’t your average “descent into madness” drama. It’s not your average DTV indie effort either, even though it does wear some dog ears due to its upstart origins. I wouldn’t dare insult anyone with hyperbole claiming it’s “unlike anything you’ve ever seen before.” But “Sound of Violence” hypnotizes with an atypical tone of unusualness that definitely differentiates it from comparable features in low-budget horror.

“Sound of Violence” is a rare kind of character study in that it actually has a narrative. “Character study” can often be code for “acting showcase built from excessive close-ups of brooding faces and other abstract imagery that barely has a plot, yet appeals to arthouse audiences who divine meaning out of self-absorbed ambiguity.” Not here. At its thematic core, “Sound of Violence” is about Alexis being consumed by destructive desires. But the film’s fiction focuses on putting purpose into her arc through story, suspense, and gruesome gore straight from a grindhouse. To put it another way, artistry doesn’t overshadow entertainment value.

Alexis is different than most cinematic serial killers, which is what makes “Sound of Violence” unique in turn. When we think of murderous maniacs in movies, they tend to be textbook villains like skin suit-wearing boogeymen or deviants who get twisted gratification out of sadomasochism. The thick brick wall of undeniable evil separating us and them bounces our perspective immediately back at us so we rarely see Buffalo Bill or whoever as anything other than a strictly psychotic monster.

“Sound of Violence” instead presents Alexis as a troubled person who almost trips into sociopathy. Or rather, she trips up a drunken attacker and inadvertently awakens a craving for carnage that soothes her senses. You don’t sympathize with Alexis. You don’t cheer her on when she tortures unwilling victims. But “Sound of Violence” explores how pain reconnects her to childhood trauma. Deafness threatens to wreck everything she’s done to rebuild herself and the fear of losing her renewed life fosters a deeper desperation to heal. The only way she knows how to do that is through sounds of struggle, which tear her heart emotionally while tearing apart targets physically.

For her first conscious crime, Alexis creates a contraption connected to a drum machine whose buttons do the dirty work for her. (This is where you have to start closing one eye to unintentional swings into silliness with Alexis having both the time and the ingenuity to devise traps worthy of Jigsaw.) Rather than relish what’s happening, Alexis turns her back to the victim and uses her music to trigger his torture. Alexis doesn’t indulge in death so much as delude herself about it. In addition to pausing to show remorseful breakdowns, “Sound of Violence” gives Alexis a dissociative characteristic that makes her more flawed than fearsome.

As “Sound of Violence” continues treading into this traditional horror territory of crazy kills, the artful edge dulls while the film teeters teasingly close to turning accidentally comical. A number of indie edges rough up believability too. Some spotty acting by supporting characters, e.g. a detective who looks like her police training consisted of watching one random “Criminal Minds” rerun, can’t wring convincingness from the procedural portion of the plot. The movie’s belt could also use tightening around the midsection, particularly with one sequence that spends too much time with a certain singer in a sound booth. A lot of slack is fortunately found in minor moments and thus isn’t at the film’s forefront. People will still snicker out loud at scenes such as the beach finale however, since “Sound of Violence’s” wallet gets in the way of fully realizing writer/director Alex Noyer semi-heady concept of visualizing violent sounds.

Regardless of warts, “Sound of Violence” mostly manages to deliver relatively relatable horror. The setting is Southern California. The people are normal. “Sound of Violence” gets carried away with kookiness infrequently, but it isn’t an interpretive amble rooted in dreamy environments or characters dunked in pretentious fantasy. “Sound of Violence” is ambitiously weird enough that it doesn’t feel formulaic. At a time when microbudget thrillers mostly play it safe, it’s worth appreciating an underdog oddball that dares to do things a little differently.

Review Score: 70

This supposedly preplanned trilogy became a tangled, bloated, inconsistent blob of inconsequential characters, dead ends, and ludicrously lame lore.