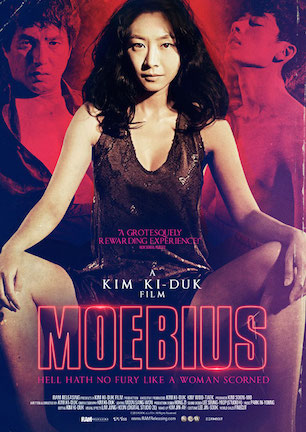

Studio: RAM Releasing

Director: Kim Ki-Duk

Writer: Kim Ki-Duk

Producer: Kim Ki-Duk, Kim woo taek, Kim soon mo

Stars: Cho jae hyun, Seo young ju, Lee eun woo

Review Score:

Summary:

A middle-class family is torn apart when a distraught wife castrates her son as retribution for her husband’s infidelity.

Review:

Two things above all else are important to know before settling into “Moebius.” The first is that while it is not a silent movie, it is a film entirely without dialogue. The second is that the central theme of its story revolves around sexual arousal in the wake of castration. So even before adding that it includes scenes of gang rape, incest, and autoerotic stimulation involving knives and rocks, “Moebius” clearly belongs in a “not for everyone” category.

Distraught over the discovery that her husband has a mistress, an unnamed wife downs a goblet of merlot, grabs a ceremonial knife hidden in the family’s Buddha statue, and enters full-on Lorena Bobbitt mode. Fortunately for the philandering husband, he wakes in time to successfully fend off his wife’s furious blade. Unfortunately for their son, she decides to castrate the boy instead.

Son now deals with the shame of being perceived as less of a man while father bears the guilt of his sins having created unintended consequences. Dad turns to the Internet as he researches ways to achieve orgasm without genitals. What he learns is that using an abrasive rock like a scouring pad against the skin can recreate sexual release, and so he teaches the technique to his son.

Are you mouthing “WTF?” yet? Wait until the son finds a willing sex partner to do the painful pleasuring for him in the form of his father’s mistress. After being gang raped by the castrated boy and some accomplices, she is all too happy to put a knife into his shoulder when he comes around again. But then she ends up turned on when she sees that throttling the blade handle back and forth results in the boy’s sexual arousal.

Still not strange enough? His guilt persisting, father decides to forego his manhood by having his penis transplanted onto his son. Apparently, the appendage has an unusual form of muscle memory, as it is later discovered that the newly reformed boy can only become erect from his mother’s touch. Needless to say, father is none too happy with this revelation. Neither was the Korean film ratings board, which had “Moebius” banned because of its salacious content.

By not having any, “Moebius” highlights how inessential a lot of dialogue often is within many motion pictures. A script devoid of verbal interaction requires impeccable visual storytelling and there is little arguing that the film succeeds with strong characterizations and a powerful plot, even without audible words.

Yet as the story grows more complicated while weaving in doctor visits, police station trips, and various other asides, the fact that no one uses their mouths to communicate becomes less of a creatively unusual stunt and more of a noticeable distraction. It is impossible to see the story as one that could honestly unfold silently in reality, which makes it a constant reminder that the film is depicting surrealistic fantasy.

On one hand, what can a father possibly say to a son who awoke to a surprise castration courtesy of his lunatic mother? On the other hand, how can a father not say anything at all?

Coherency is not the issue with “Moebius.” The true distraction is that it never shakes loose from a skin of subversive boundary pushing without a clear purpose. Seeing why an academic critic would label the presentation as bold and the ideas as provocative is easy. Much harder is justifying why audiences would willingly subject themselves to an experience designed to be this deliberately uncomfortable.

“Moebius” sends a number of mixed signals and crosses enough wires to unintentionally confuse the line between sincerity and black comedy. The film is strangely fascinated with knocking women on their backs with legs in the air and panties exposed to the repetitive point of resembling a Marx Brothers skit. Weirder still is how normal it is within the film’s world for schoolboys and for grown men to go to their knees on a whim as they pull down a boy’s pants and inspect his genitals.

Perhaps oddest of all is the arc of father teaching his castrated son how to pleasure himself. The scenario of a parent walking in on his/her child masturbating is made even more awkward when dad is the one teaching his son how to do it with a rock as well as helping to treat the wound and clean up post-climax.

Known for being controversial and experimental as an auteur filmmaker, Ki-Duk Kim’s “Moebius” ticks all the required boxes to make sure both of those adjectives still apply to the Korean writer/director. That makes his project the type of buzzed-about niche movie one sees lighting the marquee at across-town art house theaters with wine bars in their lobbies instead of candy counters and soda fountains.

By extension, the nature of that scenario means the movie itself is bound to inspire reactions dividing audiences into two distinct camps. The goatee-stroking hipster set is likely to hit the coffee shop after a screening. There they will ruminate thoughtfully about the symbolic philosophy of frustrated sexuality presented through a lens of challenging concepts and complex motivations concerning the crumbling structure of a contemporary middle-class family.

Meanwhile, those of us inspired to more pedestrian points of view are just as likely to either miss or not care what the intended takeaway is supposed to be. This is because “Moebius” makes it entirely too easy to be preoccupied with swimming against unrelenting waves of wordless weirdness drowning whatever it is the movie means to convey.

Review Score: 60

“We Bury the Dead” doesn’t have enough meat on its bones to land on a list of top ten zombie films for any of its three release years.