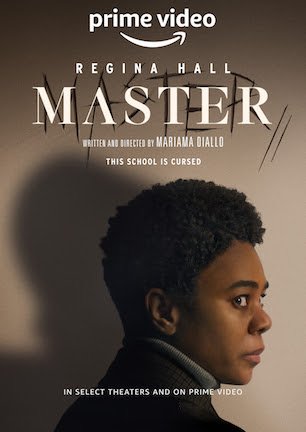

Studio: Amazon Studios

Director: Mariama Diallo

Writer: Mariama Diallo

Producer: Joshua Astrachan, Brad Becker-Parton, Andrea Roa

Stars: Regina Hall, Zoe Renee, Talia Ryder, Talia Balsam, Amber Gray, Ella Hunt, Noa Fisher, Kara Young, Bruce Altman, Jennifer Dundas, Joel de la Fuente

Review Score:

Summary:

The eerie experiences of a Black student, a dean, and a professor intersect at a predominantly white university with a haunted history.

Review:

Shortly before “Master” released wide on Prime Video, a bit of a brouhaha resulted in backlash for a critic who said he couldn’t connect with Pixar’s “Turning Red.” He felt the animated family film was tailored too specifically to Asians living in Toronto, which in turn limited its appeal.

A digital dogpile immediately ensued. Seeing that stance as obliviously ignorant discrimination, comments cynically countered with questions like, do you have to be a fish to find the heart in “Finding Nemo,” or an anthropomorphic deer to relate to the tragic loss of a parent?

This controversy came to mind when I watched “Master,” a movie that follows the intersecting arcs of three Black women in different stations at a mostly white university with a haunted history. To be perfectly frank, that “Turning Red” take reminded me that when you’re speaking about stories that represent demographics you don’t belong to, you’d better be cognizant of your cultural blindspots and tread more thoughtfully to avoid sounding tone-deaf. It’s why, as a white man covering “Master,” I hope I’m not undermining writer/director Mariama Diallo’s intentions with my take, which I also hope anyone prone to acting out of antagonism accepts in good faith.

I had the opposite thought about “Master” than the other guy had about “Turning Red.” “Master” is inextricably immersed in the experience of facing passive-aggressive, and aggressive, pressures from systemic racism at a revered institution. However, even though the story illustrates demoralizing struggles specific to Black women, you don’t need to be one yourself to be frightened by the fears they face. It isn’t merely a matter of observing from a position of privilege and applying sympathy, empathy, or even pity either. Beneath their race-based adversities lurk broader problems like disenfranchisement, gaslighting, altering personal identity to be more popularly acceptable, ignoring inconvenient truths, and avoiding conflict to keep things copacetic. These universal nightmares aren’t exclusive to gender, ethnicity, or orientation. Anyone who can’t see themselves relating to “Master’s” thematic horror is lucky to live a charmed life.

The movie’s symbols aren’t hard to see. Whether she’s the only freshman wearing an overwhelmed expression in a sea of cheerfully relaxed smiles, or sitting next to a backpack on the only empty chair in a crowded room, “Master’s” visuals repeatedly mirror new student Jasmine Moore’s gradual transformation from optimistic to ostracized.

Initially undeterred by the way fellow students treat her as a novelty, Jasmine tries to grin and bear it as best as she can. Upon finding her roommate’s friends making themselves comfortable on her bed, Jasmine attempts to endear herself by playfully inviting everyone to guess who she is. Their answers range from Beyonce to Lizzo to one of the Williams sisters as tolerance slowly leaks out of Jasmine’s disappointed laugh. It’s no coincidence that in the following scene, Jasmine wears her hair inconspicuously straight instead of sticking with the afro that made her silhouette striking.

Gail Bishop encounters similar condescension in a higher circle. Becoming the school’s first Black housemaster should inspire pride as she oversees students in Jasmine’s dorm. But leftover artifacts like a mammy cookie jar and housemaid photo found among her furnishings remind her she may be welcomed, but she may not truly belong. Self-doubt starts sapping formerly rock-solid confidence as casual comments from white peers further the nagging notion that the school may not be as separated from its problematic past as its promotional videos about diversity would have outsiders believe.

Conversely, Gail’s good friend Liv Beckman, a literature professor who is also Black, seems to have acclimated to academia. Although sympathetic to Gail’s growing frustration, Liv adopts an attitude that permits her to enjoy the perks of being a prominent professor. She teaches “The Scarlet Letter” as an allegory about racism, which confounds Jasmine since all of that book’s characters are white.

“Master” doesn’t do the best job of making Gail a maternal mentor to Jasmine. The impact of later scenes requires their relationship to be the strongest throughline in the film. Arguably, it is, but mostly in relation to how coldly other interpersonal interactions are portrayed. “Master” makes curious creative choices with scene structure, which is why we end up with several repetitive sequences of Gail jogging, yet not as many of her and Jasmine bonding.

The movie employs an unusual narrative style as it tells the tale of Jasmine feeling haunted by a legendary witch, and how her escalating mental torment pulls in Gail and Liv at opposite ends. Most of the momentum’s hiccups come from nonlinear editing. “Master” doesn’t make major leaps on its timeline, but it will try techniques such as juxtaposing concurrent scenes featuring the same character.

In one sequence, Jasmine flees from a cloaked figure while the camera also cuts back to clips of her reading worrying notes in a suicide victim’s diary. In a similar setup, two people discuss someone’s death while we simultaneously see shots of them attending a vigil for the same person. There’s no need for these events to be strictly chronological, although the more “Master” pairs two asynchronous threads together, the easier it is to lose sight of what it wants to be seen as important. Jasmine regularly experiences vivid nightmares too, so it isn’t always clear what’s a dream and what’s a quick flashback to something as simple as seeing a certain someone in a hallway.

Different people are going to get different things out of “Master” depending on what they expect and what they’re willing to take away. Hardcore horror fans hoping for uncomplicated supernatural suspense with witches, curses, and ghosts will get less than anyone else. Unlike some thrillers themed around timely topics, it’s impossible to divorce “Master’s” entertainment value from its social relevance because of how integral its commentary is to the horror’s context. There’s little leeway for interpretation to see the supposed witch as anything other than a direct metaphor for a frightening fear that influences your actions and shapes your personality.

Since movies dealing with race can be tricky to talk about, I often imagine having to head off predictable gripes from people whose faces flush red and whose boxers turn brown at words like inclusion, representation, and critical race theory. Then I try to remember that any fright film fan who finds nothing offensive about the confederate flag won’t watch “Master” in the first place. They’ll complain about it, but they won’t watch it.

For anyone open to examinations of experiences outside their everyday norms, and for those who’ve had the unpleasantness of dealing with those circumstances directly, “Master” rings a different bell of dread than a traditional horror film. You certainly don’t need to be a confused college student, a Black woman adjusting to a belittling environment, or an Asian living in Toronto to see “Master’s” message that true terror can traumatize anyone through haunting helplessness and debilitating despair.

Review Score: 70

In hindsight, maybe the more muted “28 Years Later” had to walk so the more meaningful “The Bone Temple” could run.