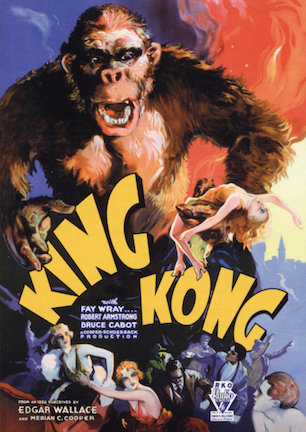

Studio: RKO Radio Pictures

Director: Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack

Writer: James Creelman, Ruth Rose

Producer: Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack

Stars: Fay Wray, Robert Armstrong, Bruce Cabot, Frank Reicher, Sam Hardy, Noble Johnson, Steve Clemento, James Flavin

Review Score:

Summary:

A filmmaker’s expedition to an uncharted island uncovers a giant ape with an unexpected attraction to a blonde starlet.

Review:

I presumed I’d be opening this look back at 1933’s “King Kong” with some sentimental ideation along the lines of, “they don’t make ‘em like this anymore!” The thing of it is, Hollywood very much does still make movies like this, although usually with one very important distinction that confuses being pretty with having personality.

Making a modern movie that encapsulates on film the sense of astonishment “King Kong” captures is practically impossible given the connected consciousness of contemporary times. “King Kong” comes from an era before Google had a satellite stationed above every possible GPS coordinate, and the unexplored globe seemingly still had wondrous mysteries to discover. When cocksure movie man Carl Denham whispers his tale of a Norwegian barque skipper selling him a map in Singapore to uncharted islands west of Sumatra, so many once faraway locales are name-dropped in the same breath that Kong’s origin is already improbably exotic.

A thieving street urchin goes from fruit filcher to aspiring starlet simply by catching the serendipitous eye of a Hollywood hotshot. A granite-jawed sailor finds love on the high seas and unexpected fame on a New York theater stage. A veteran ship captain lands on an island with a skull-shaped mountain and widens eyes at a spectacularly staged tribal ceremony that would impress Busby Berkeley and D.W. Griffith.

Impossible fantasies of all types are possible in “King Kong.” Wild dreams come true with such regularity that it is no wonder Jack Driscoll merely mutters, “dinosaur, eh?” with nearly blasé nonchalance at the sight of a downed stegosaurus. The most shock anyone verbalizes once inside the land that time forgot is a straightforward, “hey, look at that!” with the same mild enthusiasm one might manage for a Fourth of July fireworks show.

By the time Kong answers the chieftain’s gong with tree-snapping authority and log-like fingers grabbing eagerly at his fair-haired bride-to-be, the drawn out journey it took getting there, unusually fluffy even by Depression-era standards, no longer matters. 42 ape-less minutes of listing boats, potato peeling, scoping out a women’s shelter, and a lightspeed “I love you” exchange between Ann and Jack fade into forgetfulness and Kong takes control. From that moment forward, “King Kong” pours lead onto the accelerator for an unrelenting hour of action that doesn’t ease up until Kong kisses concrete in the conclusion.

George Lucas once famously said, “a special effect without a story is a pretty boring thing.” This is a dead horse to whip, but that concept highlights why virtually no one prefers his special editions to the original “Star Wars” trilogy. Overpopulating Mos Eisley’s cantina with computer-generated creatures and re-coloring X-wing lasers refreshed the visual polish. On the other side of that coin, what meaningful value the modernization added to the saga’s narrative impact is far more challenging to quantify.

Forty plus years before Lucas’ ILM would even be birthed, much less redefine the special effects standard, Willis H. O’Brien was already well aware of the symbiotic link between FX and storytelling. Everything there is to know about Kong is a story told in his epic encounter with the T-Rex. These aren’t two puppets bashing together for a basic behemoth brawl. This fight has genuine personality, and by extension, so does the movie.

Consider Kong’s opponent. Never mind that Tyrannosaurus rex literally translates to “king tyrant lizard.” The beast is a full colossal ape head taller than Kong and sports a vice-like jaw lined with carnivorous fangs. Kong is outmatched in physicality, yet undauntedly dominant in his fearlessness.

Why is Kong even fighting in the first place? Nothing says alpha male hero more than defending a distressed damsel, and the T-Rex threatening Ann is an accosting offense that cannot go unpunished. Kong doesn’t bear down with irrationally brutish force, however. Kong wisely sizes up his adversary, assesses weaknesses, and attacks with wrestling strategy that the dinosaur cannot counter because of its shape.

Kong is surprisingly calculating as a tactician, and playfully curious as a gentleman, too. When he tickles at Ann in the aftermath, it’s with a childlike inquisitiveness, and not at all like a jungle animal inspecting an unfamiliar object.

It may seem silly to infer this kind of emotion onto a character perhaps intended to impress matinee crowds of preteen children hungering for big screen monster thrills. But I would wager any amount that O’Brien and his animation team spent countless hours plotting Kong’s behavior with considerable thought and meticulous anatomical research. That effort translates into an unrivaled cinematic experience exemplifying the term classic.

Finally felling the tyrannosaur, Kong isn’t hasty in announcing his victory. He pokes at the carcass cautiously, lifts its head a few times, and plays with the jaw just to make sure. Then and only then, as if deeming the coast clear, Kong thumps his chest with a hearty roar to declare what a badass he is. It’s not unlike a bully saying, “you better run” after everyone has gone the other way, and it’s really quite hilarious to see Kong dip his toe like he is not entirely sure what just happened.

“King Kong” never takes an easy way out on its staging. At the outset of Kong’s concrete jungle rampage, there is a singular shot of a crashing car complete with a stuntman taking a spill off the sideboard. It’s such an unnecessary two seconds that you wonder why even expend the time and money to film it. But the movie is so bull-headedly determined to be the grandest visual extravaganza possible that it wants nothing more than to drown in gravy.

O’Brien never makes concessions, either. It would have been an easy matter to say, “do we really need to have Kong wrestle a giant snake?” or bargain down the workload. Kong doesn’t need to take on a tyrannosaur, a pterodactyl, and a snake any more than the Venture crew needs to run afoul of both a brontosaurus and a stegosaurus. It’s like the film cannot stop the snowball of spectacle and the audience cannot help but enjoy the entire reckless ride.

Whether trashing train tracks or inspecting bloody wounds with incredulity, “King Kong” is always focused on its star’s personal odyssey throughout the ever-escalating action. This isn’t Willis O’Brien showing off. And it isn’t “King Kong” catering to that aforementioned adolescent interest in Saturday afternoon cinema suspense. The filmmakers are constantly telling a sincere, compelling, and unexpectedly heartbreaking story about who this colossal creature truly is. That is what keeps the tale of “King Kong” timeless, even when its techniques are dated. Let’s see how many CGI-heavy blockbusters of the 21st century will enjoy the same praise in 80 years time.

Review Score: 95

Click here for Culture Crypt's review of the sequel, "Son of Kong."

Too slow to ever reach a burn, “The Dreadful” doesn’t have many logs capable of catching fire in the first place, let alone a spark to ignite them.