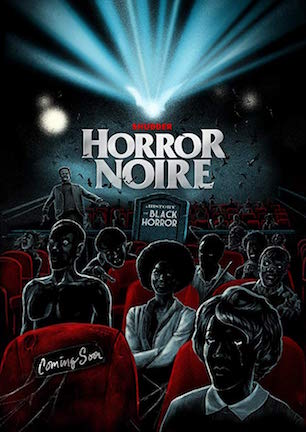

Studio: Shudder

Director: Xavier Burgin

Writer: Ashlee Blackwell, Danielle Burrows

Producer: Ashlee Blackwell, Danielle Burrows

Stars: Rusty Cundieff, Ernest Dickerson, Robin R. Means Coleman, Jordan Peele, Tananarive Due, Rachel True, Ken Foree, Keith David, Tony Todd

Review Score:

Summary:

Actors, filmmakers, authors, and academics chronicle the history of Black representation across a century of horror cinema.

Review:

When a trailer comes on TV for some hot new horror movie, my girlfriend, who does not share my rabid consumption of fright films, occasionally asks, “are you excited to see that?” It’s weird that this question still comes up because my answer always amounts to, “maybe I’m interested, but ‘excited?’ Not at all.”

Horror remains my preferred form of entertainment, but can I truly get “excited” about it anymore? Expectations open avenues for disappointment. More than that, after four decades of countless vampires, zombies, killer dolls, and haunted houses, what can the genre show me that I haven’t already seen?

Looking back on 2018, two of my top three thrillers, “Tumbbad” (review here) and “The Unthinkable” (review here), were foreign language films from unfamiliar filmmakers. That’s not commonplace for me. Upon reflection, I realized that my tastes were shifting toward unusual projects from overseas specifically because of how redundant representation had jaded me as a white, fortysomething American male. What intrigues me now are the cultures and countries that can open my imagination to new concepts from unique voices telling compelling stories.

I’m hungry to experience horror from fresh perspectives I cannot possess personally because my race, gender, or nationality does not have direct experience. For this reason, director Xavier Burgin’s documentary “Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror” legitimately excited me like no other movie on the calendar for 2019. Finally, a film to expand and inspire my knowledge, exposure, and appreciation of an often overlooked slice of cinema. “Horror Noire” at last ignites a fire under what makes the genre a uniquely exciting medium for social commentary as well as entertainment.

Based on the same named book by Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman, which is as much of a must-read as this film is a must-see, “Horror Noire” features the notable names one might expect. Included among the 21 talking heads are directors Jordan Peele, Rusty Cundieff, and Ernest Dickerson along with actors like Rachel True, Tony Todd, and Keith David. Naturally, they expound on their personal projects, e.g. “Tales from the Hood,” “Demon Knight,” “The Craft,” and “Candyman.” But additional academic insight offered by authors including Tananarive Due and Ashlee Blackwell, the latter of whom co-wrote and co-produced with Danielle Burrows, ties plentiful anecdotes together with broader contextual observations.

Burgin chooses to pair up many interviewees so that segments have more of a conversational feel than a “60 Minutes” Q&A tone. That staging sometimes seems forced. With some couples, I couldn’t tell if they were previously familiar with one another or were simply scheduled to speak on the same day. For the most part though, eliminating the need for formal narration gives “Horror Noire” an organically inviting atmosphere of friendly folks casually chatting about film.

Tananarive Due offers perhaps the most accurate summary to bridge horror fiction with horrible history by saying, “black history is black horror.” Beginning back at the birth of narrative features, “Dawn of the Dead’s” Ken Foree elaborates that many white audiences lived segregated existences where they didn’t have direct interactions with other races. For them, the portrayal of black people as dangerous threats in D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” became the dominant depiction of a group they otherwise knew little about. Presenting black culture as deviant or deficient, even metaphorically in “King Kong,” reflexively fueled racist beliefs.

That’s far from the first or last time “Horror Noire” draws lines to particular political climates, which of course remains an important theme throughout the documentary. “Get Out” played perfectly due directly to how well it fit with fears stoked during the transition between the Obama and Trump presidencies.

When ‘The Atomic Age’ moved horror into laboratories or other science settings, movies no longer needed exaggerated comic foils or household servants. Black actors thus went from playing bit background parts to disappearing completely for an entire decade.

“Horror Noire” hits a peak, more than once, when swinging spotlights onto such consequences that aren’t often considered. It probably never occurred to me that we don’t really see black characters, certainly not prominently, in the giant monster drive-in movies of the 1950s. Growing up 30 years later, it definitely never crossed my mind that the reasons for these exclusions were because studios weren’t eager to cast black performers as doctors, professors, or intellectuals of any type.

With “Night of the Living Dead’s” prominent, even if consciously unintended, parallels to the Civil Rights Movement, horror cinema began boomeranging back toward black representation in the turbulent 1960s. That morphed into blaxploitation before birthing a new era of sidekick stereotypes.

Why did Stanley Kubrick make a material change to Stephen King’s novel by killing Scatman Crothers’ Dick Halloran in “The Shining?” Why are voodoo and mysticism core components of black culture in 1980s films like “Ghost” and “The Serpent and the Rainbow?” From ‘The Magical’ and ‘The Sacrificial Negro’ tropes to the pseudo-myth about who dies first in a slasher, “Horror Noire” doesn’t merely identify clichés. It gets into why those characters are written to be black in the first place, and what being black signifies for that person on the screen.

“Horror Noire” runs by quick at just 83 minutes, but doesn’t come off as cursory. It feels like a perfect primer on the subject of black horror cinema. Its relative completeness aside, it’s impossible to not wish for an even deeper dive. I’m sure Shudder is already considering this, if not actively developing the concept, but “Horror Noire” screams to be a regular series.

Whether the filmmakers follow-up in some fashion may be irrelevant. Within minutes of end credits rolling, I was furiously Googling Oscar Michaeux, whom I’m humbled to admit I was previously unfamiliar with. I was also immediately interested in “Son of Ingagi,” the first black horror film that looks to be wildly weird as well as culturally significant. One mark of a great retrospective documentary like this one is feeling compelled to continue researching subtopics independently, in addition to coming away with a long list of excellent rental recommendations.

Most importantly, what marks “Horror Noire” as a great documentary is its ability to recalibrate what we see, what we think, and what we feel when we experience a film. When interviewees point out the importance of John Boyega’s smile at the end of “Attack the Block,” or discuss why urban settings are crucial to young people seeing their experiences reflected onscreen, we learn to see black horror, within film and without, beyond hashtags and headlines.

“Horror Noire” doesn’t push any agenda other than illumination regarding what horror movies have to say about alternative points of view. “Horror Noire” reminds us why movies are fascinating as time capsules of historical eras, but also why diverse representation matters for the betterment of evolving entertainment.

Review Score: 90

In hindsight, maybe the more muted “28 Years Later” had to walk so the more meaningful “The Bone Temple” could run.