Studio: Dimension Films

Director: Joe Chappelle

Writer: Daniel Farrands

Producer: Paul Freeman

Stars: Donald Pleasence, Paul Stephen Rudd, Marianne Hagan, Kim Darby, Bradford English, Keith Bogart, Mariah O’Brien, Leo Geter, Mitchell Ryan, J.C. Brandy, Devin Gardner, George Wilbur

Review Score:

Summary:

With Dr. Loomis and Tommy Doyle in pursuit, Michael Myers returns to Haddonfield as part of a cult conspiracy to kidnap Jamie Lloyd’s baby.

Review:

Shades of imitative inspiration exist in “The Curse of Michael Myers” that prove it partly intends to emulate the atmosphere of the original “Halloween.” Michael Myers stalks prey through a maze of white sheets flapping in a backyard wind. A scary sprint across the street culminates in frantic door pounding while Michael bears down in silhouette. The movie practically lifts storyboards directly from John Carpenter’s classic, though it at least demonstrates devotion to making this sixth installment feel distinctly like “Halloween.”

Concurrently, “Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers” also has an agenda to deliver a marketable-to-the-mainstream horror movie. This dippy desire is what dunks “Halloween 6” into the derivative depths of photocopied scenes and patchwork plotting hastily conceived with poor execution.

By the time any horror series is six films deep, sequels are predominantly preaching to a choir of dedicated patronage. Smart strategy is to strive for pleasing the devil you know without an arrogant assumption of wooing new viewers en masse by increasing accessibility through milquetoast appeal.

“Halloween 6” initially promised to unify the multi-movie mythology and set the story straight for longtime fans with longstanding questions. Instead, the film’s theatrical cut mucked up continuity so much more that subsequent sequels started over by looking the other way.

If focus group futzing is at fault, then you have to think Dimension put too much faith in test screening comment cards filled in by the casually confused rather than the franchise faithful. Reshoots and reedits thus resulted in a neutered edition of the movie that satisfies no one, filmmakers and filmgoers alike.

Room 237 Easter egg pays tribute to "The Shining."

“Halloween 6” takes the breadcrumbs of backstory other sequels only dropped and walked away from, e.g. the Samhain reference from “Halloween II” and the Man in Black from “Halloween 5,” and tries stirring a stew of cult conspiracy insanity to explain Michael Myers’ origin as an unstoppable monster. It’s admirable that screenwriter Daniel Farrands even attempts to make all of the various pieces fit, even though they most certainly do not.

Some of that fault falls on Farrands. To get his setup where he wants/needs it, retroactive revisionism results in more head-scratching details than can be counted. Michael Myers had a babysitter on the 1963 night when he murdered his sister Judith? Unlikely, but okay. That blank can be filled in by assuming Michael was across the street at Mrs. Blankenship’s before wandering back home to put on his clown mask and pick up a kitchen knife.

Less easily explained is how the Strode family now lives in the Myers house, yet four out of five of them don’t even know it, even when everyone else in town does. Everywhere in the United States, infamous serial killer homes are destroyed not long after their crimes, if for no other reason than to exorcise the neighborhood of lookie-loos and souvenir seekers curious for a macabre peek into the past. Everywhere except for Haddonfield.

The Myers house stood vacant from (presumably) Michael’s first murder in 1963 through his most recent rampage in 1989. During the 26 years in between, the well-known residence became the site of angry mob rallies, test of courage dares, childish vandalism, even more murders. So how is it that some pint-size pranksters know enough to deface the property in the present using an effigy of Michael, yet the current family is oblivious to their dwelling’s creepy connection with their own relative, Laurie Strode?

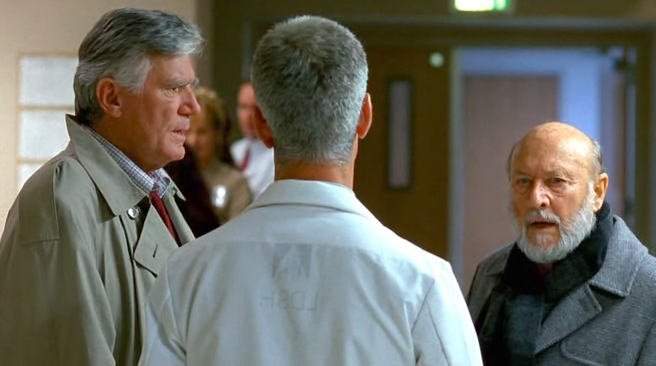

Blame for broader stroke butchery goes beyond Farrands’ original intent and into the offices of whoever made the decision to create a reedited cut in the first place. Donald Pleasence’s final portrayal of Dr. Loomis is sadly reduced to a cameo fighting for meaningful function against truncated screen time. And in concocting a conclusion that might make more sense to those confounded by the complexities of runes, star charts, and Celtic legends, the theatrical cut ironically ends up with a more confusing ending by making mumbled references to genetic engineering, lab experiments, and whatever green goo ends up oozing out of Michael Myers’ mask.

Haddonfield steals its medical scrubs from Latter Day Saints Hospital in Utah.

“Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers” further waters down any flavor in its feel with enough flickering lights, strobe effects, and lightning flashes to give an epileptic 40 seizures. Standard setups such as having to step over the killer’s body while he lies still on the ground, a hand from behind grabbing a shoulder on cue with an audio sting, or an insert shot of a hand creeping toward a doorknob choke the movie into tapping out early from establishing its style as inspired or original.

The movie misfires on other technical levels too, even music. That should be hard for a “Halloween” film to screw up, yet composer Alan Howarth uncharacteristically supplements the signature synth score with jarring “whhhnnnggg-whhhnnnggg-whhnngg!!” electric guitar screams and rolling tom-tom drums that could only sound more out of place if they added a circus slide whistle.

So why does a film fighting battles of quality on multiple fronts earn a higher rating than better-regarded “Halloween” sequels like parts four and five? In its release year of 1995, “Halloween 6” was a critical and commercial disappointment. But it is a movie with a convoluted genesis and final delivery so unusual, it becomes a highly intriguing hindsight watch from a 21st-century viewpoint.

The first thing making “Halloween 6” interesting in retrospect is the entire “Producer’s Cut” versus “Theatrical Cut” debacle, exhaustive details of which are covered elsewhere. Seeing the differences between the two versions with the advantage of insight into what motivated change choices is flat-out fascinating from a film fan’s perspective. Bonkers scene splices take on new life as imaginative curiosities instead of being dismissible as careless inclusions or post-production shenanigans.

“Halloween 6” is also hilariously dated to its 1995 release year. Watch as a junior college campus erupts in wild applause for mouthy talk radio host Barry Simms and remember that this was an era of shock jock celebrity. Gaze at the glory of a DOS font display on Tommy Doyle’s CRT monitor and ask, did computers really look that bad back then? Ponder casting and costuming choices that have John Strode looking like a blonde George Wendt while his wife Debra resembles Vicki Lawrence from “Mama’s Family” without a flower print housedress.

Paul Rudd's Tommy Doyle is a fan of John Waters stable staple Divine.

Another captivating component of a decades-after-the-fact viewing is peeking at an early appearance of the movie’s second-billed star. “Friday the 13th” boasts a pre-fame Kevin Bacon. “A Nightmare on Elm Street” has Johnny Depp. “Texas Chainsaw Massacre” counts Viggo Mortensen, Matthew McConaughey, and Renee Zellweger among its previously unknown alumni. “Halloween” of course has Jamie Lee Curtis. But it also has Paul Stephen Rudd (as he is credited in the “Halloween 6” theatrical cut).

Paul Rudd’s performance in “Halloween 6” is downright bizarre. Count the number of facial expressions Rudd runs through during a Michael Myers confrontation as his character, Tommy Doyle, rescues Kara Strode from confinement in the climax. Now try and figure out what in the world he is supposed to be conveying. Rudd’s entire personification of Tommy is a constantly bewildering oscillation between socially awkward, mentally unhinged, violently volatile, occasionally affectionate, and generally just all over the place.

Across-the-street boogeyman sightings aside, Tommy Doyle only came face-to-face with Michael Myers one time as a boy, which was right before Laurie Strode had he and Lindsey Wallace hide in a closet. There is trauma in that experience, although Tommy never even saw Michael draw blood, much less witness him creating a corpse. To be this much of an obsessive, unstable weirdo 17 years after that single encounter is a significant stretch.

If this were the last anyone ever saw of Paul Rudd onscreen, he might have been written off as a bad actor. Yet knowing the talent and charisma he has since brought to roles like “Ant-Man” or any number of terrific comedies, you instead wonder if the excessive oddities on display here are more deliberate than they seem. Maybe this is unrecognized genius gestating as unrefined technique, and director Joe Chappelle never saw fit to recalibrate questionable characterization choices.

Having always cited “Halloween” as my personal favorite of the high profile horror franchises, I was at the time as peeved as anyone with the “Drink Your Ovaltine” reveal of what “The Curse of Michael Myers” was versus what it was supposed to be. It doesn’t have to be that way any more.

Its initial punch of disappointment softened by letdowns that came later, and its slight charms bolstered by the benefit of fresh eyes in retrospect, the theatrical cut of “Halloween 6” is more than the meager movie many remember. Maybe not much more, and maybe not on the level of the “Producer’s Cut.” But given the choice between parts four, five, and six for which sequel I would most want to revisit, I would pick “Halloween 6” without hesitation.

Review Score: 65

Compelling performances keep “Hallow Road” swimming as strongly as possible against the strong current of a drowsy pace.